With all the talk about deep learning and neural networks, I thought it'd be fun to revisit one of my favorite applications of artificial neural networks (ANNs) -- dynamic branch prediction.

Instruction Pipelines

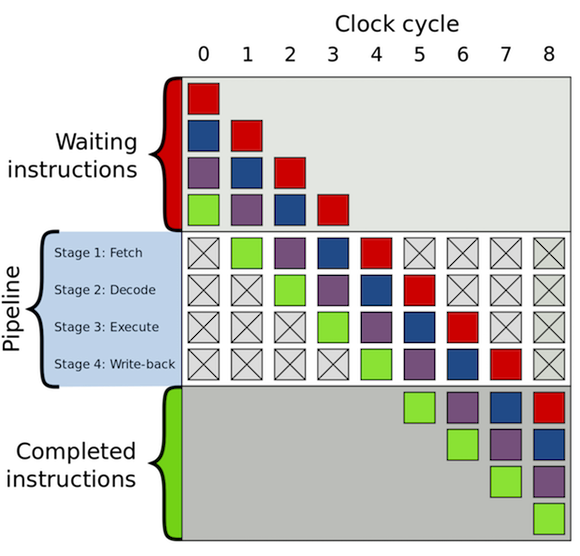

To understand what branch predication is and why it's needed, we first need to take a look at how CPUs process instructions. A cycle in a CPU is often broken up into a series of steps known as the instruction pipeline, creating a form of parallelism within the CPU as shown below.

An example of a simple instruction pipeline: Fetching the instruction,

decoding it, executing it, and writing the value back to memory. Image source

An example of a simple instruction pipeline: Fetching the instruction,

decoding it, executing it, and writing the value back to memory. Image source

Branches are a problem because the jump to a different area of code in memory can not be determined until that specific instruction is executed, potentially making the instructions in the pipeline after it useless and leading to a loss of precious CPU cycles.

All of this can be avoided by having branch prediction logic as instructions are being read. A predictor can be as simple as predicting that the branch will always/never be taken and become as complex as a multi-layer perceptron.

Perceptrons

The perceptron, which dates back to 1957, is the simplest example of an ANN, learning a binary (meaning either 0 or 1, yes or no, etc.) classifier based on a set of binary inputs, a set of weights for each input, and a single threshold.

Lets take the example shown above. We want the decision (the output) made by the perceptron to be related to each of the inputs. To do this mathematically, we can just add all those inputs together. But what if we want to ignore one of the inputs? This is where the set of the weights for each input comes into play. Adjusting the weight to be closer to 0 means that input should have little impact on the overall decision. Adjusting the weight to be very large either negatively or positively means that input should have a very strong impact on the overall decision. Putting it all together, if we were to compute the impact it would look something like this:

$$ \mbox{output} = x_1 * w_1 + x_2 * w_2 + x_3 * w_3 $$

To turn this sum into either a 0 (no) or 1 (yes), we can apply a cutoff

point or a threshold to the sum. For instance, if we have a threshold of 5

and \(\mbox{output} \leq 5\) it will be classified as 1. If the

\(\mbox{output} \gt 5\) then it will be classified as 1. This can be more

compactly respresented with the following equation:

$$ \begin{eqnarray} \mbox{output} & = & \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & \mbox{if} \sum_i x_i * w_i \leq \mbox{threshold} \\ 1 & \mbox{if} \sum_i x_i * w_i > \mbox{threshold} \end{array} \right . \end{eqnarray} $$

We may understand the perceptron mathematically, but what does it mean when used in decision making? Say we want to use a perceptron to create a model of whether we should eat a bowl of ice cream for breakfast. We could weigh that decision using several different factors:

- Is it chocolate ice cream?

- Is it a warm summer day?

- Are you going on a run today?

Each one of these factors may be more or less important than the other. Perhaps a bowl of ice cream is a preemptive reward for a run and you will not eat it otherwise, meaning #3 would be highly weighted while the others would be not.

You can think of the threshold as how much all the factors contribute to your

overall motivation to each a bowl of ice cream. For example, if you have a

threshold of 0, then eating the ice cream is an easy decision, almost

regardless of the inputs. If you have a higher threshold, then it will take

more motivation from each of those factors before you make your decision. By

varying the number of inputs, weights for each input, and the overall threshold

you can create all sorts of different decision-making models, and not just for

ice cream!

Learning from the Past

Now that we know a little more about perceptrons, this section will apply these concepts to branch prediction. Learning from branch prediction is straightforward since we know whether we made the right prediction right after the branch occurs.

The first instance of using neural networks for branch prediction appeared around the year 2000, in a paper titled "Dynamic Branch Prediction with Perceptrons". It proposed a method that used perceptrons to learn the correlations behind the history of the branch and the outcome of a branch. The intuition is that the history of whether a branch was taken or not taken in the past could have bearing on whether this branch will be taken now. An example of this in action would be in code loops where we iterate over many items and make some sort of check.

So how does this work? First we need to answer some questions:

- How do you encode a history of branches?

- How is this information passed to the perceptron for a prediction?

Global History Register (GHR)

If we consider a the outcome of a branch as a binary output (either taken or

not) we can represent the history of that branch as a series of bits. For

example, if the first time a branch is seen its taken, we start off with 0000 0001. Then if it's not taken taken, we have 0000 0010. As we take more

branches, we continually shift the history left and capture the outcome of the

branch.

Now when a branch is being considered, we can now use the history as inputs to our perceptron. But what about the weights? And how do we take it account right/wrong predictions after a branch happens?

Training the Perceptron

Once the perceptron makes a prediction we can use it and the actual outcome of the branch as a means to adjust the input weights and train the perceptron.

Intuitively, if a piece of the branch history has a positive correlation to whether a branch is predicted taken we want the weight for that input to be large. If there is negative correlation, we want the weight for that input to be negative. And if there is a weak or no correlation, the weight should remain close to 0 so that it contributes little to the final output of the perceptron.

In the example below, to make our math a little easier, we'll treat a branch

being taken as 1 and not taken as -1. The actual outcome will increment the weight if it agrees and decrement if it disagrees -- satisfying our intuition above.

And that's all there is to it! As time goes on, the perceptron sees more and more branches creating a correlation (or negative correlation) in the inputs and weights with the ultimate outcome of the branch.

If you're interested in learning more about the branch predictor and the paper goes much more in-depth on how this is can be done in hardware and also provides a nice comparison to other techniques.

The branch less taken

While Jiménez finds that the perceptron predictor has a lower misprediction rate on all except two different benchmarks when compared to two other techniques, we don't really see the perceptron predictor in modern day CPUs despite being used in most state of the art prediction schemes. A quick search brought up a press release from AMD that touts "Neural Net Prediction", but not much else.

A major disadvantage and one that may be the biggest blocker to uptake of the perceptron predictor is the increased computational complexity when compared to the relatively simple counters used in other techniques. This overhead may not be worth it when there are easier ways to add CPU performance, such as additional cores, increased L1/L2 caches, and/or single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) instructions.

Thanks for taking the time! I hope you enjoyed reading and learning about the application of perceptrons in the world of branch prediction.